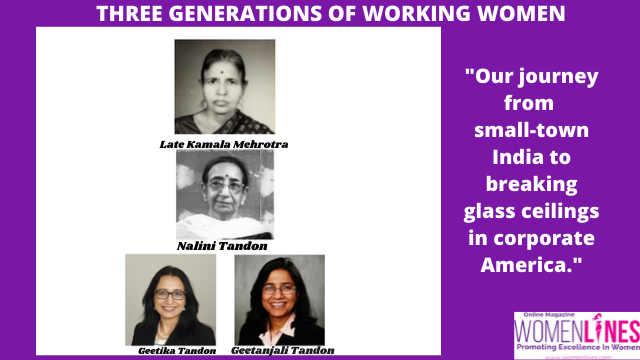

Womenlines takes pleasure to share the real-life inspiring stories of three generations of working women and welcomes Nalini Tandon, Geetika Tandon and Geetanjali Tandon as guest contributors in Womenlines.

American Novelist, Louisa May Alcott once said – “Nothing is impossible to a determined woman”! The story shared below proves this saying very well! The story starts with the exceptional journey of Kamala Mehrotra, who despite the challenges faced by womenfolk during the pre-independence era of India was able to complete double bachelor’s and master’s degrees in education (B. Ed. and M. Ed.). She retired as the Director of the Bureau of Psychology at Allahabad University, India. Kamala’s daughter Nalini Tandon was successful in completing her medical studies and post-graduation. She had an illustrious career as a Medical Commissioner and retired as a Chief Medical Officer at Employees State Insurance Corporation (ESIC), India. Nalini worked hard and her determination helped her to grow up the ranks, overcoming the challenges working women faced in her era. Geetika and Geetanjali have taken a step further and have become a beacon of hope for women aspiring to excel in corporate life. They grew up fighting the societal mindset which discouraged higher studies for girls and favoured sons over daughters. Both of them have beaten all odds and are successfully breaking glass ceilings in corporate America today.

Women, like men, have been working since the origin of the human race. But the “working woman” embodies vastly different challenges from the “woman working at home.” Those few small steps that women took outside the boundaries of their homes have meant large personal struggles and huge social, economic, and cultural revolutions—bloodless, nonviolent, but revolutions, nonetheless.

Here is a story of a 100-year-old revolution that spanned three generations—from 1920s pre-independence India to the corporate USA. You won’t have to look very hard to find your story here too.

Kamala’s story (1923–2011)

Picture pre-independence India—colonial rule with its attendant inequalities and impacts on economic and social growth in the country and a struggle for freedom that further led to unrest in political and social thought.

Kamala, the second of eight children, was born in March 1923 to Gaya Prasad Tandon ( a school teacher)and Sunder. For a girl born in a lower-middle-class family in India during the third decade of the twentieth century, the chances of acquiring any sort of education were almost nonexistent. That would have been Kamala’s fate too had it not been for the conviction of her father, who believed that women had as much right to education as men.

As a son born before her had been lost to illness, Kamala’s birth was not much of an occasion to celebrate, but Gaya Prasad welcomed her, just as he welcomed each child he was blessed with.

Kamala reminisces in her memoirs, “In the pre-1947 era, women in our society and family background were hardly educated. No woman in our family had ever even attended primary school, let alone college. They led a domestic life, cooking or indulging in religious activities.”

“Our schools had no desks or chairs. We sat on the ground on mats and wrote on wooden pallets with straw pens, dipping them in white kharia and later ink.”

This was Kamala’s primary education until the age of nine. In 1937, she topped the Uttar Pradesh Board Examination for grade six (held those days under British rule). Despite vehement protests from his wife and other family members, Gaya Prasad allowed Kamala to stay in the Mahila College hostel to continue her studies. Little did he know that he was not just educating a brilliant daughter, he was spawning generations of empowerment for the women in his family.

Under her father’s championship and the tutelage of very sincere and efficient teachers, Kamala completed Class 12, standing fourth in Class 10 UP Board Examination and sixth in the Class 12 examination. She was 19 years old, a ripe age for marriage.

Her father, under immense pressure from his family to fix Kamala’s marriage, put forth one condition for the potential bridegroom: “My daughter will continue her education, and you will ensure that there are no hurdles.” Laxman Prasad Mehrotra agreed, and in June 1943, Kamala married him with the blessings of both families. With her father’s and her husband’s support, Kamala completed her Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) and Master of Arts (M.A.) degrees from Lucknow University.

However, her education was hard-won in the orthodox setup, where the daughter-in-law’s role was confined to her marital home, taking care of a large joint family. Whenever Kamala left home to attend college, the womenfolk would mock her with snide remarks, “Dekho, bahuria padhe jaat hai” (Look, the daughter-in-law of the house is going to college). This mockery continued with Kamala’s ineptness with household chores, something she had not learned well because most of her adult life was spent in dorms and boarding homes. Nevertheless, her husband was her rock of support and encouraged her to continue studying. Kamala went on to further complete double bachelor’s and master’s degrees in education (B. Ed. and M. Ed.).

This was 1948–49, the dawn of India’s independence, which also gave birth to the Education department of Allahabad University. Impressed by Kamala’s credentials, the Vice-Chancellor of the University offered her the post of part-time lecturer for B.Ed. students while she completed her M.Ed. She was also expecting her first child at this time and stayed with relatives or in a hostel while she studied, worked, and nurtured life within her.

The advent of a daughter three months after Kamala completed her M.Ed. and the allotment of a university quarter heralded a new chapter in her life. After returning from maternity leave, Kamala was selected as an assistant professor at the Department of Education at the University of Allahabad. She later joined the job of Senior Tester in the Bureau of Psychology, a department for research and training in Psychology.

Kamala was the only married woman in Bank Road, Allahabad who worked outside her home—and the first “working woman” on both sides of the family. She coped with the challenges of managing work, home, and family with no time-saving appliances, refrigerators, or pressure cookers. Full-time and part-time paid help, and some support from her children helped her to meet the challenges of daily life.

Kamala belonged to an era where she could not have achieved her ambitions without the approval and support of her male allies: her father and her husband. Despite the scorn and ridicule that she often faced—sadly, more from the women—she carved a path for herself, a path that few women of the time would even dream of.

As Michele Norris says, “Women who want to change the world or go as far as their talents and interests take them, sometimes have to resist or reject that little voice in their head that stokes our insecurities and suggests how we should or shouldn’t behave.”

Kamala retired as the Director of the Bureau of Psychology at Allahabad University, serving in her role with honesty and dedication.

Nalini’s story (1949–present)

Kamala’s eldest daughter, Nalini, remembers her childhood. “I remember sometimes wistfully thinking, ‘Why does my mother work? All my friends’ mothers are at home when they return from school, and they get hot snacks to eat.’ It was much later that I began respecting her and admiring that she was capable of so much more.

“She was the one who supervised our homework, instilled the love of books in us, told us bedtime stories, and ensured that we were punctual. She had a fetish for cleanliness and punctuality, and all of us siblings have inherited it.” Nalini recounts the lessons she has learned from her mother’s experiences. “Persevere and thou shalt achieve! Do not be deterred by criticism and adverse circumstances. Firm support from those who matter is a bonus that always helps.”

Nalini acknowledges that she had several advantages over her mother right from birth. She was born in independent India, where the emancipation of women was at least being talked about, if not practised. Her father’s family was open to the idea of educating women, although earning your own living was still very rare. Nalini and her three siblings were educated in good schools. After completing her school education, she elected to train as a doctor. She completed her medical studies at Lady Harding Medical College in December 1972 and married Prabhat in January 1973.

Soon after marriage, she began her internship at Lady Harding Hospital (now Sucheta Kriplani Hospital). It was gruelling work, comprising 36-hour rotations, and then a bus journey back home to take care of the myriad chores of running a household.

“That summer, I was posted at Najafgarh, an urban village which was part of the Delhi metro area. We stayed on the premises of the small community hospital at the edge of the village. We made field trips in an open jeep, which was often out of gas. Thus, instead of the jeep taking us to patients, we often ended up pushing the jeep to the destination. The dispensaries at these sites were very primitive with an acute scarcity of medicines.” It was an exhausting time for Nalini—long and arduous daily commutes in the scorching summer heat, weekends loaded with household responsibilities, night shifts, and hardly any time to relax and let go.

In June 1974, she gave birth to her first daughter—born on the day Nalini was supposed to start her residency program. “Everyone congratulated us, sharing our happiness. However, I was taken aback and extremely annoyed when my cousin’s husband remarked, ‘Ladki ho gayee! Ek laakh ki degree aa gayee!’ I learned that day that people have such extraordinary medieval notions about daughters.”

She further reminisces, “It is heart-wrenching for a mother to leave her little baby and go to work, and when that work entails leaving the home for 24 to 48 hours at a time, it pricks your conscience. My husband and my entire family rallied to support me. Though I went to work, I often fretted about why there were no daycare centres at the hospital where new mothers could feed their babies. In those days, there were no breast pumps, so I could only breastfeed my child for a very short span of five to six months.”

Nalini gave birth to her second daughter in November 1977. “My husband and I were very happy, but my mother-in-law was a little disappointed. No one directly congratulated me this time, except my close friend. It seemed as if giving birth to another daughter was a calamity.”

Nalini went on to apply for jobs and for an M.D. degree. She received the offer to do postgraduation twice—once in Anatomy and later in Pathology. However, she was pregnant at both those times and had to let those opportunities go. “What you postpone in life, you seldom get a chance to attain again. The opportunity passes you by. Although I did postgraduation later, it was never in a clinical subject.”

In December 1975, Nalini began working as a Medical Officer at Employees State Insurance Corporation (ESIC). The job suited her requirements, and she worked there for 34 years. Nalini retired as Chief Medical Officer and Medical Commissioner with ESIC and later completed her Masters in Public Health from the Washington University in St Louis.

Gender discrimination at work is as old as the working woman, and Nalini faced several frustrating battles. “I was given an out-of-turn chance to hold an important portfolio at our Corporate office, as Deputy Medical Commissioner. This became a source of envy for my colleagues and some of my seniors. Gradually, I noticed that I was not being given opportunities to attend conferences or be part of important inspection tours to various parts of India—only my male colleagues, who were junior to me, were being sent. When I discussed this with my then boss, a woman, I received this astounding reply. ‘You have to take care of your husband and children. The male doctors have no such problems; thus, they are selected.’ I had to convince her that my family responsibilities were my personal issue, and the decision should be taken based solely on my performance at work. I was not in the habit of speaking up for myself and that became a deterrent for me. The idea that women should take care of their homes, despite them being high achievers, was still the prevalent mindset in India of the 1980s.”

In addition to discrimination at work, maintaining a work-life balance was challenging for Nalini. Her daughters were young, and her husband developed very brittle diabetes with several episodes of hypoglycemia, especially at night. However, Nalini forged ahead, taking one step at a time. “I managed to overcome many hurdles and prospered in my career, receiving promotions and accolades through the passing decades.”

She adds, “Relatives and my extended support system helped to bring up my children. A working woman in India in those days, and perhaps still, requires a lot of help from friends and family to continue working if she desires to have a family of her own. She is fraught with guilt—for not being there for her family, for not cooking quality food, for missing important milestones in her child’s life (I missed most of my elder daughter’s milestones), for always being obligated to others, for relegating her precious children to the care of hired help.”

Nalini sums up her journey thus:

“Life is never a straight line. Even those who face no hurdles in choosing a career will be tested by the travesties of life. Be prepared to face them. A supporting family goes a long way in helping you to achieve your dreams!”

Geetika’s story (1974–present)

Geetika and her younger sister, Geetanjali, grew up in a conflicting world, in the city of Delhi, where modern ideas clashed with traditional culture and an enduring and beautiful past. The 1970s and 1980s were also India’s adolescent years when it began adopting new ways of thinking. In that atmosphere, the two girls embraced “radical” feminist ideals—ideals that their own grandmother and mother had fought hard to even think about.

Geetika remembers their small apartment in New Delhi, India. She remembers her mother working hard at her job as a doctor as well as performing her role as a dutiful wife, mother, and daughter-in-law in an Indian household.

“My home was traditional and yet nontraditional. It is hard to describe, but it was my mother’s innate feminism that inspired our strong belief that women are equal, if not better than men, and you shall never forget that.

“For as long as I can remember, I felt that I needed to fight the world for equality. Indian society and culture are so full of misogynistic and patriarchal norms that it was hard to not revolt against everything I came across. I drew little or no solace from religion, although because of growing up in a Catholic school and Hindu household, I did manage to develop a personal relationship with a force that needed to exist for my own sanity. Growing up in a culture that is innately filled with stories about God and avatars performing all kinds of feats was only possible with a strong belief in science and logic. I cannot remember a time when I was not enamoured by science and its amazing discoveries and inventions. I had a lot of questions, and science had the answers. In fact, only science had any real answers. Everything else was draped in tradition and culture.”

Both Geetika and Geetanjali were excellent students, ambitious and fiercely competitive. They completed part of their studies in India and came to the US at different times.

While Geetika’s family had been supportive all through, and waves of modern thinking were crashing against the walls of tradition in India, it was never smooth sailing. Even when Geetika’s parents were helping her apply to US universities for postgraduation, there were the occasional relatives and friends who would say, “Why are you wasting money? Why don’t you get her married instead?”

After completing her undergraduate degree in Architecture in India, Geetika did a double master’s degree in Architecture and Building Science from the University of Southern California and a master’s degree in computer science from the University of California, Santa Barbara. She got married to Pankaj in 1997.

She started her work life as a software engineer at IBM. Within a year of joining IBM, she gave birth to a daughter. “While I was still trying to settle into my career, I was also struggling as a new mother trying to balance home, child, and work. I was lucky to be surrounded by a family support system and a partner who helped me cope. As I progressed in my job to the role of an Executive IT Architect. During this time, I gave birth to a son in 2005 and was then managing two young children at home along with work.”

Geetika acknowledges that she is part of a generation of Indian women who had an unprecedented opportunity to learn and grow, who were children of the Information Age with huge exposure to the world through media, travel, and IT.

“However, little did I realize that with all the advantages came the burden of living up to the image of the mythical “superwoman”—the woman who could be a superior homemaker, a model mother, a glamorous life partner, and an ambitious career achiever.” Slowly, she realized that societal expectations of women hadn’t changed despite all the education and progress.

“A senior executive once asked me about how we make it work as a dual-career couple. After I was done telling him about our arrangement, he rolled his eyes and said, “Thank Goodness my wife does not work!” There was still a vast difference between the expectations from men and women; and glass ceilings and workplace discrimination were still very real, especially for minority women in the US.

Geetika struggled to keep up, and it was a stressful time for her. “I remember one day after a stressful day at work, as I was walking to my car, my house helper called and told me that she could not make it. I had an hour-long commute ahead of me and now would also have to cook dinner, and then get back to work. I was sleepy and exhausted. I sat in my car in the parking lot and cried my heart out. But then I grit my teeth and drove back home – ordered out food for the family and got back to work. I was deeply cognizant of the fact that as a third-generation working woman, I have a tremendous responsibility. My grandmother and mother were pioneers who shattered myths and fought the establishment and thereby became trailblazers for us. It was our responsibility to persevere and open new avenues for the women of the next generation. And persevere I did!”

Geetika sums up the ups and downs of her career with: “It’s not how many times you get knocked down that counts, it’s how many times you get back up”

Geetika is currently Managing Director with Deloitte Consulting where she leads large-scale technology implementations. She continues to promote the cause of women through her work with various nonprofits and professional organizations.

Geetanjali’s story (1977–present)

Geetanjali, Geetika’s younger sister, learned several different lessons in her journey from being the “baby of the family” to where she is today. “When I came into middle school, I felt the first twinge of having a working mother when my mother’s work hours changed, and she would be back only by 6 p.m. instead of the earlier 2 p.m. I had many more school years to go, and I was on the brink of being a teenager. I now had to come back home alone, prepare my lunch, and keep up with my studies. That period gave me the confidence to manage things on my own and made me comfortable with being by myself.”

Geetanjali experienced gender discrimination as she grew up but never gave it much thought. She recalls a time when her father’s friend came to visit them. After having met the two girls, he remarked “Oh, you have two daughters. Don’t you want a son?” Her father replied, “These daughters are my sons.” Geetanjali remembers that incident even today because “What my father said was very important for me. I was too young to even understand why people preferred sons.”

Geetanjali strongly believes in letting people make their choices and respecting that choice—stay at home or work, have babies or not, get married or not.

In the same vein, she doesn’t like expectations to be forced upon her. This strong, independent streak led to her choice of hotel management as a career option. Her parents were supportive even though they had their doubts. To pursue the course she had chosen, Geetanjali left home at the age of 17 for her undergraduate education. “This was the late 1990s, and there was open discrimination. The girls’ hostel was locked by 8 p.m. while boys could stay out until midnight or even later.”

Geetanjali was the first single woman in her family to leave India and join a US university. “My parents’ trust was a huge responsibility for me. I did not know any other girl around me (even among my friends) who had the choices I was given.”

In the US, Geetanjali finished her undergraduate studies in 2000 and went on to do her post-graduation in Agricultural Economics. She met her would-be husband at this time, and they got married in February 2003.

Geetanjali and her husband were working in different cities even after their marriage. She moved to be with him only when she found a job in his city. Three years later, Paragdecided to go back to University for his PhD, and in a role reversal from traditional expectations, Geetanjali became the primary breadwinner.

In 2009, Geetanjali had her first child. She had decided to study for an executive MBA degree while her husband was in the final year of his PhD. Her husband’s constant support and encouragement helped her along the way.

While life as a full-time professional couple had been smoother, the journey of a working mother was beset with challenges. “Not being able to spend late hours at work, feeling the guilt of taking away time from my child… and the first tug of subtle discrimination. At work, there was no one to advise me because around me were successful men or women with stay-at-home wives or husbands, single women, or married women with no children. I realized that for all the talk of diversity and support for working mothers, the real everyday management of home and work for working moms is very hard.”

Geetanjali and her partner have worked through these challenges as a dual-career couple, rather than as a working mom or dad. When her husband looked for a position, he narrowed his choices to cities that had options for Geetanjali as well. Geetanjali divided her professional life between telecommuting and physically commuting to work. They were clear that both their careers and their family were equally important, and both of them would have to make sacrifices and manage their time.

“Mothers still take up a lot more of the extra work of raising children, such as registering for extracurricular activities, planning birthday parties, or coordinating playdates, and I am learning not to feel guilty for not being able to do more. Sometimes, I feel we put tremendous pressure on ourselves to excel at everything. My grandmother and mother fought hard to get us here so we could live the way we want to, but we are still shaping our lives and choices based on society’s expectations. Our job is to make it easier for the next generation. I hope the next generation of women can take all these bridges and add their own bridge to this river. We have to keep building that bridge.”

The journey goes on with Geetanjali’s elder daughter who is now looking at career choices. “She wants to be a marine biologist and work at the research centre being built by the Jacques Cousteau Foundation at the bottom of the ocean next to Brazil. Excitedly, I told her I’d come and visit when she was working there. She looked at me and said, ‘But I want a family too. So, I will have to make choices.’”

“Would a 12-year-old boy think of his prospective family if this were his dream?” Geetanjali questions. Her firm message to her daughter: “Pursue your dreams. Everything else will fall in place.”

Geetanjali is currently Senior Vice President in Finance at Ceridian and is passionate about her profession as well as making corporate policies more women and family-friendly. She continues to be a champion of DEI initiatives and has influenced the change in policies through them

The story continues…

The story of these four women is the stories of millions of women around the world, who work hard to carve their identities, fulfil their dreams, take care of their homes and families, and sometimes, just survive. The pandemic has brought about an unparalleled regression in the careers of many women. An entire generation of women could be hurt as they have had to drop out of the workforce to take care of children. Those that drop out often have trouble getting back in, and the longer they stay out, the harder it is.

There is worse rampant discrimination against women all around the world. It can be in the harrowing form of forced female feticide and infanticide, genital cutting and mutilation, inability to abort or use family planning measures, being forced to stay indoors or wear burkhas or chadors, being denied education and financial independence, getting no or insufficient maternity leave, or just being blatantly ridiculed. Social media, too, has its share of disrespect and downright ridicule for women.

We hope this story inspires all women to persevere despite all the challenges life throws at them. We still have a long way to go. These are just a few steps in the right direction.

Are you looking out for tools, strategies and tips to become a better version of yourself! Subscribe to powerful weekly content on leadership, health and business excellence at https://www.womenlines.com NOW!

Also read: Overcoming Limiting Beliefs

Follow Womenlines on Social Media

Subscribe to Womenlines, the top-ranked online magazine for business, health, and leadership insights. Unleash your true potential with captivating content, and witness our expert content marketing services skyrocket your brand’s online visibility worldwide. Join us on this transformative journey to becoming your best self!

Subscribe to Womenlines, the top-ranked online magazine for business, health, and leadership insights. Unleash your true potential with captivating content, and witness our expert content marketing services skyrocket your brand’s online visibility worldwide. Join us on this transformative journey to becoming your best self!